Transforming African Museums: News from the Field

Held from 28 to 30 January 2025 at Louvre Abu Dhabi and produced by France Muséums, the symposium “African Museums Today & Tomorrow” brought together some thirty professionals from across the African continent, the African diaspora, and institutions in Europe and North America. Its aim? To provide a unique space for reflection on the changes occurring in African museums, discussed by those who transform them on a daily basis.

This article revisits the exchanges that took place in the symposium and highlights the key lessons for museum institutions across the world.

Redefine the narratives: a museum imperative

The symposium first revealed a shared priority: the desire to revisit institutional narratives often rooted in frameworks inherited from the colonial period, in order to reconnect them with contemporary societies. In Kinshasa, the National Museums in the Democratic Republic of Congo renounced ethnic divisions in its displays in favour of transversal presentations that highlight the fluidity of cultures. In Dakar, the Musée Théodore Monod d’Art Africain, IFAN Cheikh Anta Diop, is exploring new ways to narrate the collections using a participatory approach with the assistance of artists and cultural professionals.

For El Hadji Malick Ndiaye, Head of the Museums Department and Curator of the Musée Théodore Monod d’Art Africain IFAN-CAD, this transformation in the role of museums involves the co-creation of meaning:

“We have undertaken to partner with artists as mediators and to co-create something new, with the goal of updating the narrative of the objects, of reassessing them, and of reinserting the museum in the social fabric. […] To transform the museum into a space for the living rather than it being a container for inanimate objects”.

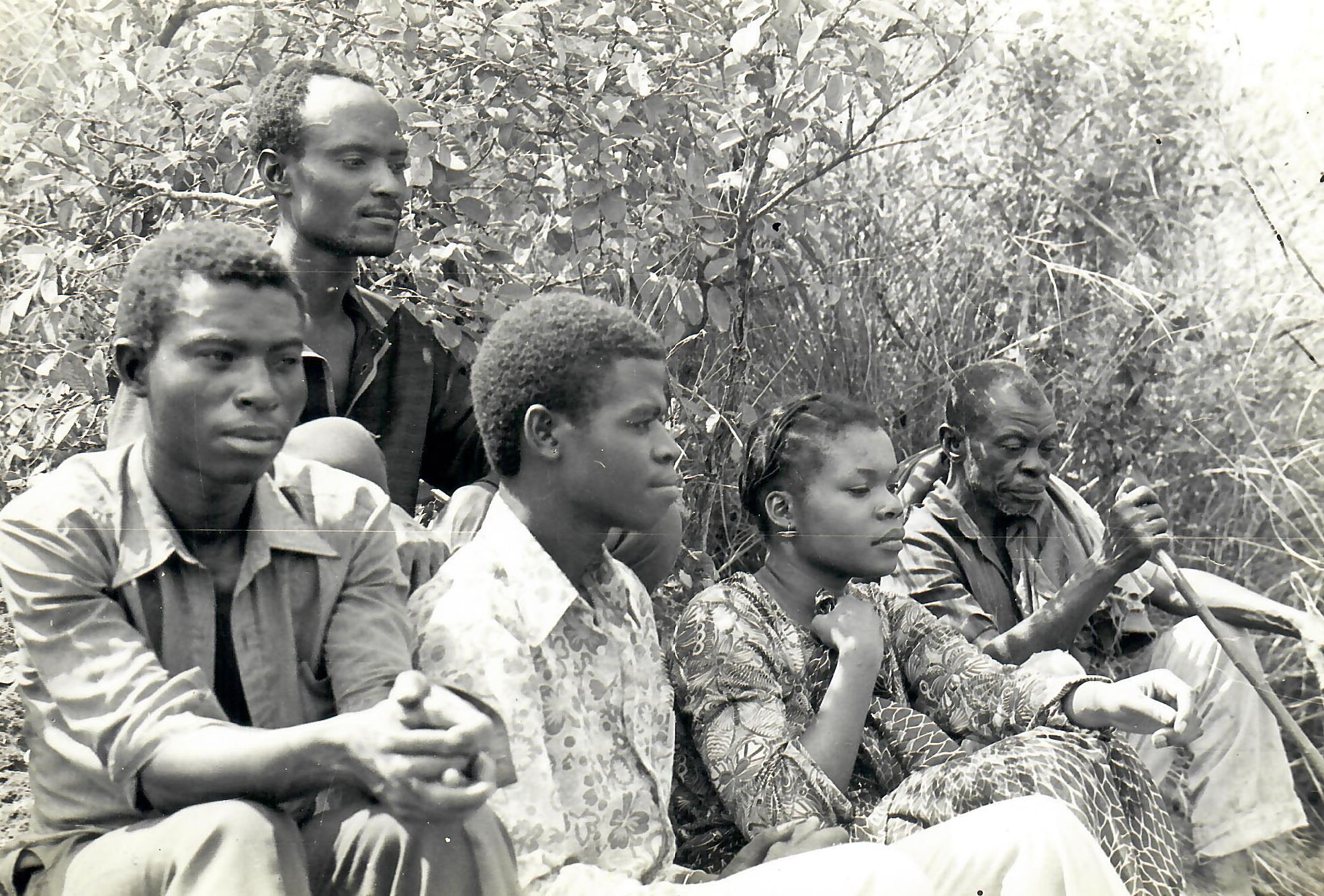

In South Africa, the Reimagining Iziko Museums project also illustrates this dynamic. It gives professionals the freedom to question the practices and reconfigure the narratives in institutions that were open during apartheid.

In every case, “changing the narrative” is not simply a question of adjustment but a profound reconstitution.

Youth and engagement: building the future of museums

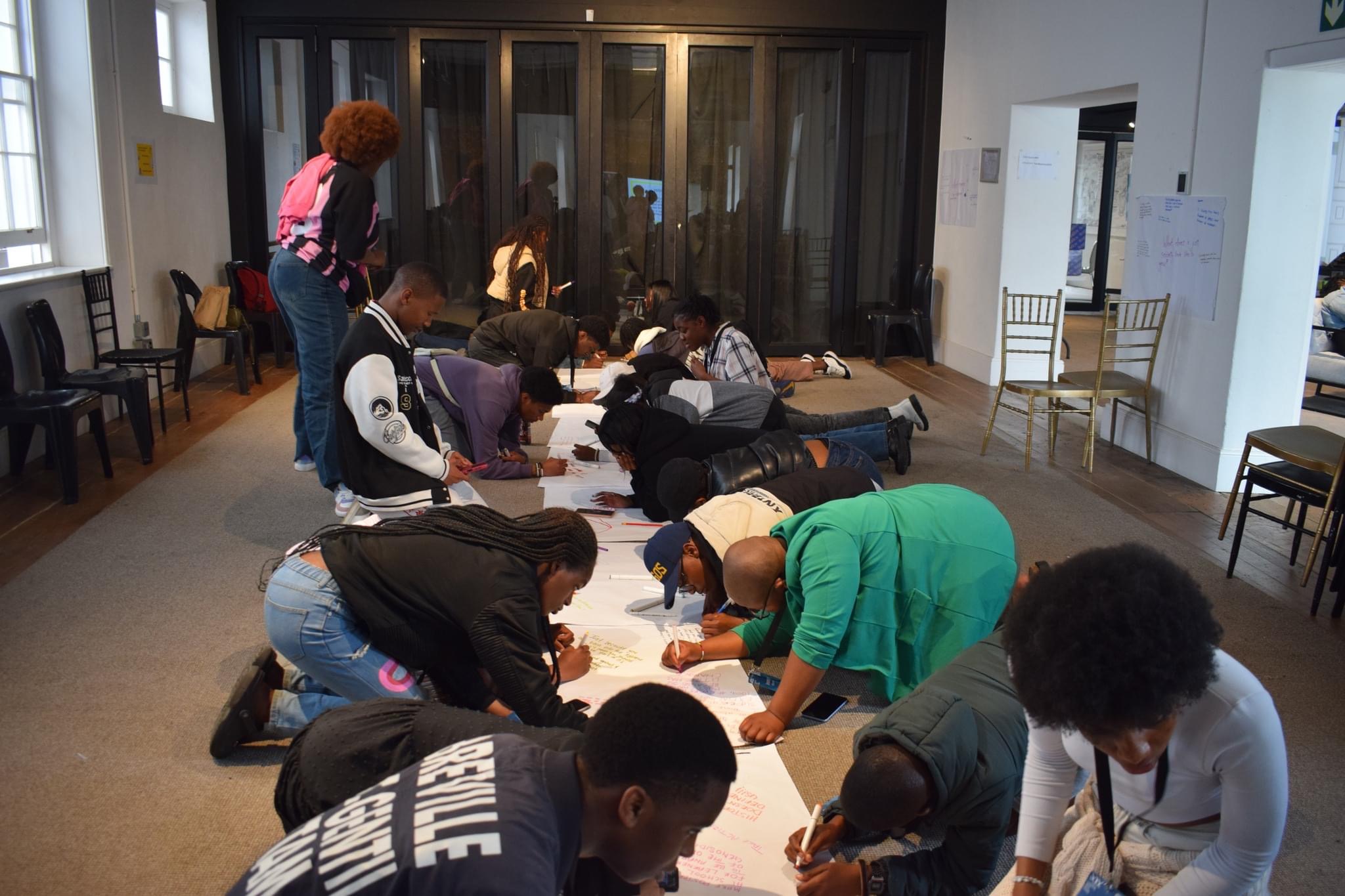

One of the main focuses of the symposium was the importance of engaging the museum with its environment, especially by involving young people in the museum-making process. In Niamey, the Musée National Boubou-Hama has set up a learning and vocational training centre that aids young people excluded from the formal education system. And Kenya’s national museums offer spaces to those aged from 20 to 35 to create and experiment with business development strategies.

Samuel Sidibé, the director of Mali’s National Zoo in Bamako, pointed out that these initiatives must be rooted in global dynamics; young people are connected to the world and cultural institutions must be too, if they wish to reach them:

“The Malian diaspora is everywhere and Malian culture is expressed through it. The questions asked by young people are more than national questions”.

Charlene Houston, from the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation in Cape Town, South Africa, insists on the importance of suitable narrative tools and of an institution that is both open to debate and a driving force to stimulate a sense of citizenship:

“It is important for young people to know the history of the country so that they can understand what point we are at in our history, currently. They can learn from the past by rereading it through their own lenses and thus acquire tools, develop skills and values that will take them further as they embark on struggles to make a better life for themselves. […] Museums must be places of interaction and reciprocal exchange”.

These views reflect a shared conviction: that the young are not a passive public to be instructed, but active participants with new narratives.

Collections in movement, communities in dialogue

Throughout the discussions, a shared belief became apparent: collections can no longer be regarded as fixed, nor disconnected from the societies that gave rise to them. Through the roundtable discussion “Collections, Transmissions, Connections”, the participants endorsed a more inclusive and human-centred approach to conservation.

Referring to her experience at the Moto Moto Museum in Zambia, which she directed for seven years, Perrice Nkombwe emphasised the potential of museums to become motors of social cohesion. She underlined their capacity to affect the entire social fabric by supporting the local economy, promoting health, and taking part in processes of reconciliation and healing after conflict.

“Museums explore culture in its entirety and can therefore succeed in bringing together people with different beliefs or apprehensions, helping them to understand our work.”.

Genuine dialogue with communities also entails accepting that certain objects may temporarily leave collections to travel and valuing local knowledge of traditional conservation methods. This openness calls for a redefinition of standards, particularly for African works held outside the continent.

On this subject, several institutions questioned the relevance of the standards in force in Western museums. For example, the MARKK in Hamburg is currently examining how its conservation standards might be adapted to facilitate the exchange of works and make loan processes more inclusive and collaborative.

Barbara Plankensteiner, director of the MARKK in Hamburg, questioned: “How can we move from object-oriented conservation practices to more people-oriented conservation practices? There is still a long way to go there, but it is still necessary, and also to consider local knowledge on how objects are handled or should be preserved.”.

These reflections combine with practical concerns: how can works be made more accessible? How can intercontinental loans be facilitated without imposing inappropriate standards? And, above all, how can communities regain their objects and narratives? These questions underpin a transformation of museum institutions in which conservation can become a tool for dialogue.

Scientific research and the construction of a national identity

Another key symposium focus was the need to give scientific research more importance in African museums. Long sidelined or answerable to management elsewhere, this research is now reacquiring significance, not only to document collections, but also to anchor museums more deeply in their societies.

For Hugues Heumen Tchana, director of the Musée National du Cameroun, in Yaoundé, Cameroon, such a development necessitates a redefinition of heritage itself:

“There is no such thing as a superior culture, and even less so an inferior one. It is essential that contemporaneity be documented and contemporary art be collected for culture to be framed within a heritage perspective”.

Beyond the preservation of objects, a museum has a mission to pass on knowledge and traditional know-how to successive generations, to educate the community (its younger members in particular), and to expand awareness of the value of heritage. By understanding the importance of its tangible and intangible heritage, and by knowing its history, a community is invested with a unifying sense of pride that will help it build a better future.

Josette Shaje Tshiluila, professor of anthropology at Kinshasa University and a researcher at the Institute of National Museums of Congo in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, observed:

“Researching our heritage can cultivate bonds—bonds based on knowledge about objects but also about others. For me, this is essential for Africa”.

This approach also implies active community involvement in heritage-making processes. Every day, researchers, curators and academics are thus redefining the role of the museum in Africa’s intellectual and civic ecosystem. The museum becomes both a producer of knowledge and a facilitator of cultural ownership.

Rebalancing international cooperation

The symposium also offered a synopsis of the dynamics of “North–South” cooperation between international institutions. While questions of restitution remain pivotal, speakers pointed up the emergence of more horizontal relationships. The Dakar Declaration, signed in 2023 by 60 African and European institutions, represents a significant advance on this matter.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou, president of the Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac in Paris, stated:

“Museums are constantly being reimagined; the word remains the same, but the realities evolve. It is clear that we are now in an era of international collaboration, and that no-one still holds a monopoly on knowledge or the narrative. I believe that, going forward, we must also relinquish any monopoly over the objects. The objects too should be able to circulate freely”.

And Mehdi Qotbi, visual artist and president of the Fondation nationale des Musées du Maroc (Morocco’s National Museums Foundation – FNM), reminded the audience that cultural partnerships also serve as upholders of sovereignty:

“For African countries, investing in the development of museums and cultural institutions is one way to reclaim their narratives, to assert their heritage, and to champion their place in global cultural exchanges”.

This rebalancing of relations is accompanied by an increase in “South–South” cooperation, leading to more flexible interactions, managed by the museum professionals themselves, and without having to pass through public institutions or other bodies.

Contemporary art as a force for transformation

Long almost absent from African museums, contemporary art today has a growing presence. It is recognised for its appeal across the generations, its capacity to question prevailing narratives, and its ability to stimulate collective healing.

In spite of past programmes to support contemporary art, Africa’s museums never embraced an active policy to promote it. Accordingly, African artists took the initiative, creating their own spaces for exhibitions and exchange to display their work. Bandjoun Station cultural centre has thus turned into an essential venue in Cameroon’s cultural and artistic landscape.

New museum projects are being worked on to welcome contemporary art.

Olivia Anani, Executive Secretary to the prefiguration committee of the Museum of Contemporary Arts in Cotonou (MACC) in Benin, commented:

“Thinking about contemporary art as a way to bring people together, connecting communities through the exploration of diverse forms of knowledge, holds healing potential”.

Many projects are seeing the light of day, such as the museum in Cotonou, the Norval Foundation in South Africa, Bandjoun Station in Cameroon, and the Cité de la culture africaine, Musée du continent in Rabat. These institutions no longer separate art from society; instead, they draw strength from the connection to challenge norms and unite generations.

The museum as social hub

As the symposium’s different contributions were made, a clear observation became apparent: African museums are not attempting to replicate existing models but to invent new formats rooted in dialogue, diversity, and the circulation of knowledge.

By bringing together voices too seldom heard on such a scale, the symposium allowed this transition to be documented.

For France Muséums, the executive producer of this event for Louvre Abu Dhabi, this project reflects a long-term commitment to supporting cultural institutions around the world in their strategic thinking.