Interview – The importance of research in the construction of a cultural identity, with Josette Shaje a Tshiluila

Interview 4/6: “The importance of research in the construction of a cultural identity”, with Josette Shaje a Tshiluila

For this fourth episode of our series on the conference African Museums: Today and Tomorrow, produced by France Muséums for Louvre Abu Dhabi in January 2025, we sat down for a talk with Josette Shaje a Tshiluila. As one of the participants in the round table Relocating Research, in the interview she revisited the subject of the role of research in the renewal of collections and heritage narratives on the African continent.

Josette Shaje a Tshiluila is a professor of anthropology at Kinshasa University in the DRC. A member of the Institute of National Museums of Congo (INMC) since 1973, she was its assistant Deputy General from 1987 to 1997 and its General Director from 2004 to 2006. She contributed to building up the institution’s collections through the many missions she carried out as part of her research into Congolese heritage.

Can you tell us about the history and missions of the Institute of National Museums of Congo (INMC)?

The INMC was created in 1970 by order of the president to protect the works of art, monuments, archaeological sites and objects whose preservation is in the public’s historical, artistic and scientific interest. The institution manages state-owned museums, such as the National Museum of Lubumbashi, the National Museum of Kananga, and the National Museum of Mbandaka. The institute also has an educational purpose: it trains young people to continue the work initiated by previous generations.

I began working at the INMC during a period of cultural vitality. It was a time when a vision of heritage was taking shape: its protection, promotion, and the role it should play on a national and an international scale. It was the period of the Festivals of Negro Arts in Dakar, in Nigeria, and there was the large World Conference of Art Critics held in Kinshasa. Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor and the concept of Négritude were of great influence, as were the innovative ideas and writings of Senegalese intellectual Cheikh Anta Diop.

The delicate issue of the restitution of artworks was a major concern at that time, and a report on it was even presented to the United Nations in October 1974. However, many people thought it was not of major importance to recover objects from other countries when there were so many available to us locally. The belief was that if we were to focus on those already on our soil, it would be easier for us to obtain the scientific and contextual information we needed to do our research effectively.

The goal of the INMC then was to recruit young academics to train them in the fields of the objects collection, research, and heritage and its identification. Notions of finance were also addressed in order to purchase heritage objects from local peoples and collectors. Calls went out for applications, and I responded. I began by spending two years as an assistant intern. At the end of that period, my application to work there officially was accepted and it was then that my research really began.

What was the nature of your research at the Institute?

The research programme was carried out in collaboration with Belgian institutions, including the museum in Tervuren (Royal Museum for Central Africa, now AfricaMuseum) and the University of Brussels. Thus, the team was made up of young Congolese and Belgian researchers.

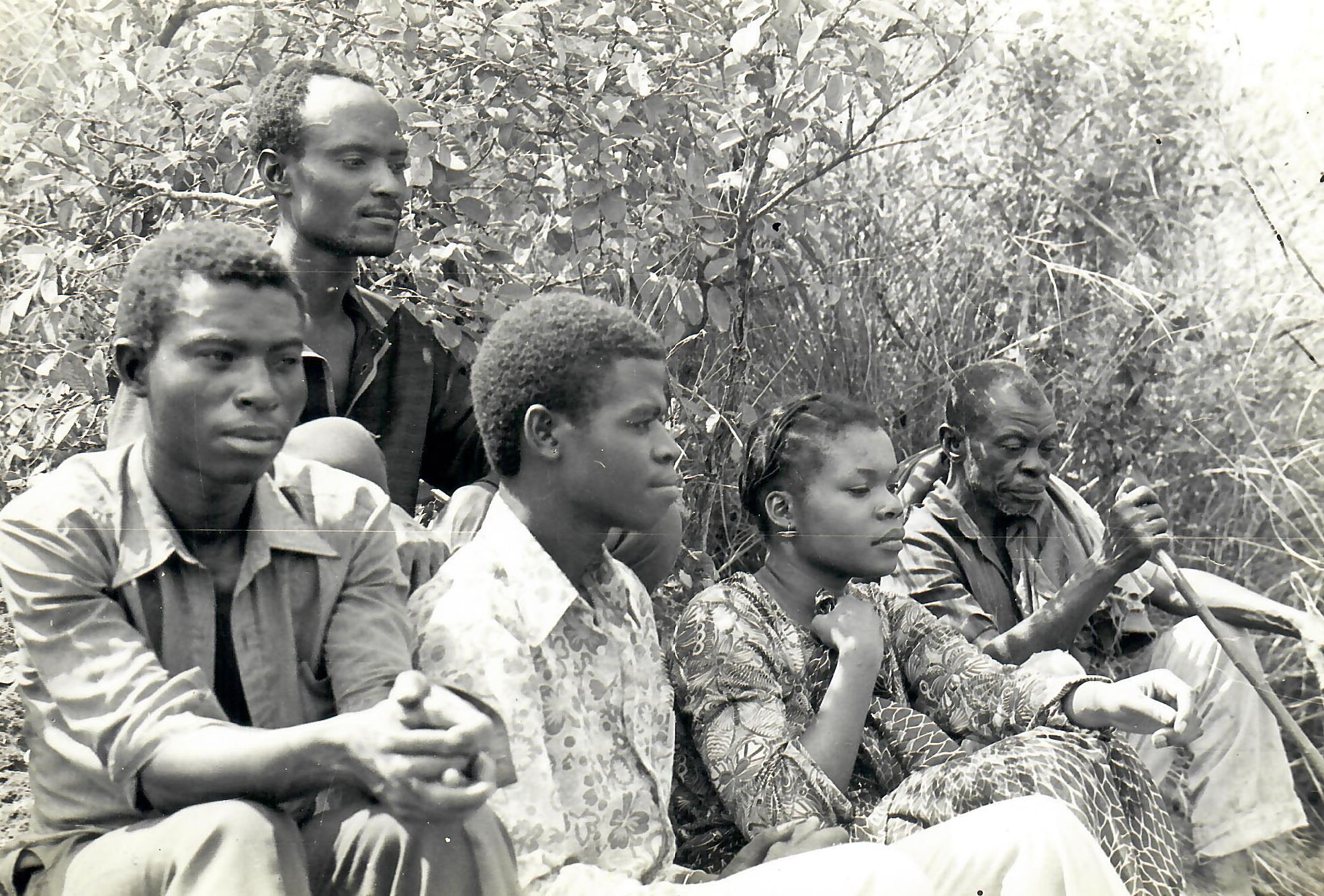

Our work consisted of collecting objects from the artistic and cultural heritage – both tangible and non-tangible – and bringing them to the museum for preservation and research. To do so, we crisscrossed the whole of the DRC to meet communities, and we would stay with them, sometimes for several months, long enough to create a stable and close contact with the different peoples. We had to explain our work and the reasons for the collecting, and then bring back objects to the museum. We also had regular contact with private collectors: we would visit them directly and see if their objects were suitably interesting for the museum. If so, we would buy them.

In this way, we were able to create a department of traditional art, for whose various sections we were responsible. Subsequently, we created a department of contemporary art because, in addition to the question of restitutions, we were also interested in contemporary production.

We ended up making regular visits to the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa, where we purchased works exhibited by artists. The President of the Republic also promoted Congolese artists, regularly offering his guests works of contemporary Congolese art.

In what ways have the collection and research of objects been vital to defining the identity of the country?

The concept of identity often cropped up when I began my research at the INMC. We had to live and bring out this identity in order to build it up and also to validate its legitimacy. I remember the numerous festivals and events organised at which representatives of different ethnic groups were invited to demonstrate their traditional practices: they would dance, play music… These were ways for them to express their cultural identity, so that we could fully embrace it. It’s essential to understand that it is when you lose your identity that others find ways to defeat you. Our work in collecting and researching Congolese heritage strengthened this impetus.

The construction of cultural identity also involved reinforcing existing links between communities. As I moved around the various territories, I had the opportunity to create strong bonds that connected me to the places I visited. Collecting objects became a relationship between myself and the peoples. Researching our heritage can cultivate bonds—bonds based on knowledge about objects but also about others. For me, this is essential for Africa.

WHAT ROLE DOES THE MUSEUM PLAY IN THIS OUTLOOK?

A museum’s principal vocation is to create links between generations through the transmission of memory. Many of the people I meet in my research work, or those who visit the museum, are aware of this: they have told me that knowing that their objects were preserved in the museum reassured them.

Museums can also create links with the generations yet to come by passing on significant messages about objects.

For example, while I was at the Symposium, I heard about an exhibition in a gallery in Cameroon, in which the artist highlighted the use of machetes in the construction of homes. In the DRC, machetes are traditionally used by farmers but young people are beginning to use them in acts of violence. Remembering that machetes can be used to build rather than destroy can be a lesson; a cultural message that we are able to transmit. Objects in museums can thus take on a positive significance.

Museums in Africa can focus on conveying messages that make a positive contribution rather than those that detract.

Why are these spaces for dialogue, like the Abu Dhabi conference, so important?

My feeling is that this Symposium, like the exhibition “Kings and Queens of Africa: Forms and Figures of Power” currently being presented at Louvre Abu Dhabi, revolve around the same subject: what museum for Africa? This is not a new question, it was already tackled in a series of meetings titled “What Museums for Africa? Heritage in the Future”, organised by ICOM in Benin, Ghana and Togo in 1991. The meetings held in Abu Dhabi in January allowed us to openly discuss important questions through the prism of today’s challenges.

Such events are very important as they give us the chance to take a step back and reflect calmly on issues linked to history and society. This type of round table encourages questions and provides direction for them to be considered in a more positive way and for improvements to be made. These encounters are also a means to pass on knowledge to the generations that will follow us.

To learn more about the conference produced by France Muséums for Louvre Abu Dhabi